1.Born to Race in the Ocean: A Biological Marvel

If marine fish were compared to vehicles, tuna would undoubtedly be the top “Ferrari” – their streamlined torpedo-shaped bodies reduce water resistance, and their special swimming muscle groups give them ultimate efficiency. Some species can reach speeds of up to 75 kilometers per hour (about 47 miles per hour), equivalent to the speed of a car on a highway. Even more astonishingly, tuna, along with moonfish and mako sharks, are among the few fish species on Earth that can maintain a body temperature higher than the water temperature. This endothermic trait enables them to remain active in the vast ocean, free from the constraints of environmental temperature.

The tuna family is characterized by significant differences in size: the smallest, the bullet tuna, is only 50 centimeters long and weighs less than 2 kilograms, while the Atlantic bluefin tuna can grow up to 4.6 meters and weigh up to 684 kilograms, with a lifespan of up to 50 years, comparable to that of an adult horse. Their sensory and physiological structures are specifically adapted for predation – the bigeye tuna has an eye diameter of up to 10 centimeters, allowing it to adapt to the weak light environment at depths of 400 to 800 meters, and it undertakes vertical migrations between day and night in search of prey. As top predators in the ocean, their trophic level is as high as 4.2 to 4.5, exceeding that of the great white shark at 4.0, and they consume up to 8 to 10% of their body weight daily, feeding on mid-upper layer fish such as sardines and squid, maintaining the balance of the marine ecosystem.

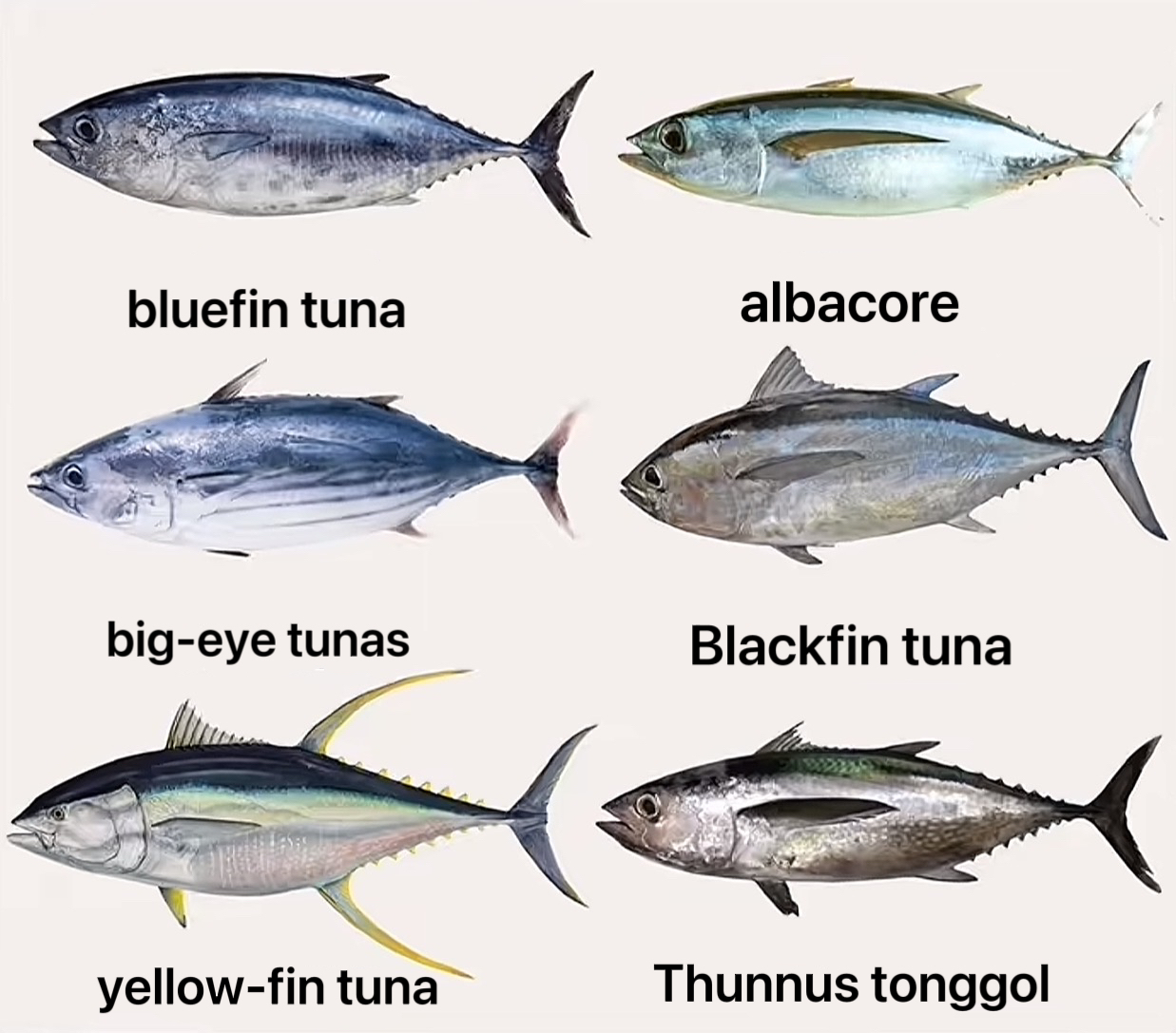

2.Family Tree: Classification of 15 Tuna Species and Market Stars

In taxonomy, tuna belongs to the order Perciformes, family Scombridae, and the genus Thunnus (Thunnini tribe), comprising 5 genera and 15 species. The core species are divided into “true tuna” and other groups. Among them, the seven species with the highest commercial value are known as “major market tuna” and dominate global fishery trade:

- Skipjack: accounting for over 50% of global tuna catches, it is the main ingredient for canned tuna, with an affordable price and relatively stable resources;

- Yellowfin: with a catch rate of about 30%, it has tender meat and is a common ingredient in sushi restaurants as well as a popular choice for grilling;

- Bigeye: highly favored for its excellent raw eating quality, but its vertical migration habit makes it vulnerable to longline fishing, and its population is under pressure from overfishing;

- Albacore: renowned for its high content of Omega-3 fatty acids, it is often processed into high-end canned tuna;

- The three bluefin tuna: Atlantic, Pacific, and Southern bluefin tuna, although accounting for only 1% of global catches, are highly sought after in the top sushi market and command high prices. Among them, the Southern bluefin tuna has been listed as an endangered species.

The origin of the word “tuna” has a cross-cultural flavor, derived from the Latin “thunnus”, which traces back to the Greek “θύννος” (thýnnos), meaning “to rush”, precisely fitting its high-speed swimming characteristic. In many European languages, such as French “thon”, Spanish “atún”, and Italian “tonno”, all stem from this root, reflecting humanity’s long-term recognition of this fish.

3. Transoceanic Migration: A 9,000-Kilometer Navigation Miracle

Tuna are among the greatest migrators in the ocean. Some populations undertake transoceanic journeys each year that rival human circumnavigations. The migration of the Pacific bluefin tuna is a prime example: they are born in Japanese waters, then cross the entire Pacific Ocean to feed off the coast of California, USA, and return to their birthplace to reproduce as adults, covering a distance of up to 9,000 kilometers. Their navigation system, guided by the Earth’s magnetic field, ensures that their migration path has an error of no more than 50 kilometers.

This large-scale migration is not only a survival strategy but also an important part of the ecological cycle. Tuna schools can number in the tens of thousands, forming spectacular “fish balls” to defend against predators, while transferring energy and nutrients between different oceanic regions. As apex predators, they control the population of their prey, preventing the overpopulation of a single species and the resulting ecological imbalance. Their existence directly affects the stability of the marine food chain.

4.Value and Crisis: From Table Delicacy to Survival Predicament

Tuna is an important source of protein for millions of people around the world and is one of the most commercially valuable marine fish. In 2022, the global tuna catch reached 5.2 million tons. In 2010 alone, the United States imported 314,000 tons, worth 1.3 billion US dollars. The main fishing method is purse seine (accounting for 66%), followed by longline fishing (9%), but the latter has a high bycatch rate of 28%, leading to the accidental death of marine life such as sea turtles and sharks, posing an ecological threat.

Overfishing is the greatest threat to tuna: the population of Southern Bluefin Tuna has declined by 78% to 90% between 1956 and 2016; Pacific Bluefin Tuna has decreased by 17% to 24% between 1952 and 2018; and the populations of Bigeye Tuna and Yellowfin Tuna in the Indian Ocean are still overfished. Globally, 13% of tuna populations have been identified as overfished, and some populations have a development rate exceeding the maximum sustainable yield, increasing the risk of resource depletion. In addition, factors such as rising water temperatures due to global warming and oil spills polluting spawning grounds have further deteriorated their living environment.

5.Protecting Bluefin: Exploring the Path to Sustainability and Hope

In the face of the crisis, the international community has taken multiple protective measures: limiting catch volumes, controlling the size of fishing fleets, and setting clear resource allocation quotas. Some coastal countries have strengthened management by regulating access to exclusive economic zones for fishing and charging fishing fees. The World Wildlife Fund (WWF) and the International Seafood Sustainability Foundation (ISSF) have collaborated to promote the transformation of the fishing industry through the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) certification system, encouraging sustainable fishing practices.

Positive signals are emerging: the 2024 ISSF report shows that the proportion of healthy tuna populations globally has increased to 88%, while the proportion of overfished populations has dropped to 10%. The populations of Eastern Pacific Yellowfin Tuna and Atlantic Longfin Tuna have significantly improved. However, the situation of Indian Ocean populations remains unresolved, and the recovery of bluefin tuna still requires long-term efforts. For consumers, choosing MSC-certified tuna products and refraining from consuming endangered species are also important ways to participate in protection.

From the “swift runner” in ancient Greek to a “keystone species” in modern marine ecology, the fate of tuna is closely linked to human activities. This marine creature, which combines speed and strength, is both a masterpiece of natural evolution and a “barometer” of ocean health. Protecting tuna is essentially about safeguarding the biodiversity and ecological balance of the ocean, ensuring the continuation of this “marine Ferrari” legend.